What the heck is a Zero-Knowledge Proof, anyway?

Whenever public blockchains are brought up, two big criticisms follow close behind: “They don’t scale!” goes the first one, and “There’s absolutely no privacy!” goes the second.

Maybe public blockchains offer great censorship resistance, but if they can’t scale and keep transactions private, how will they ever reach the masses?

There’s a lot of truth to these criticisms, and we’ve been searching for solutions for nearly a decade. Plenty of sharp engineers went on to build new blockchains for this reason, cleverly restructuring them so they could scale more elegantly than Bitcoin and Ethereum. But there are no free lunches, as they say. Scalability comes at a cost, and it’s a steep one — the trade-off is decentralization and security.

Until now.

It might sound too good to be true, but a revolutionary technology called “zero-knowledge proofs” seems to have solved both of these problems.

We’ll get into the weeds in a moment, but for now, know that zero-knowledge technology helps us scale blockchains by compressing data while still being able to verify its authenticity. Projects such as zkSync and Loopring are building zk-rollups on Ethereum to do just that.

Zero-knowledge technology also maintains privacy because everyone can verify the authenticity of data, even though they can’t access the underlying data. Projects like Aztec are building a privacy layer for Ethereum using zero-knowledge technology.

So, this is exciting stuff!

But understanding how it works is no simple feat. Most people who try to learn about zero-knowledge technology don’t get very far. After all, it’s a complicated topic that requires a lot of math and cryptography knowledge just to begin making sense of it.

That brings us to this article. Without getting bogged down in the complexities of zero-knowledge proofs, we’ll get to the big picture and build an intuition around it through digestible examples. Consider this the first part in a series unraveling zero-knowledge proofs, from overviews to details.

Without further ado, let’s get started!

What is a Zero-Knowledge Proof?

A zero-knowledge proof is a method that allows one party (Peggy) to prove to another (Victor) that she knows a secret value that fulfills some constraints — without revealing any additional information to Victor, only that she knows this secret value.

In a zero-knowledge protocol, we refer to the secret value as the “witness” and the two parties as the “Prover” and “Verifier”.

- Prover: The prover (“Peggy”) wants to prove to the verifier (“Victor”) that she knows the witness without revealing the witness.

- Verifier: The verifier (“Victor”) needs to verify that the prover does know the witness without revealing the witness to himself or anyone else.

For a zero-knowledge protocol to be valid, it has to satisfy three properties:

- Completeness: If the proof is valid, it must be accepted by the verifier (ie. a correct proof is always accepted).

- Soundness: If the proof is invalid, it must be rejected by the verifier (ie. the probability that a verifier accepts an incorrect solution is negligible).

- Zero-Knowledge: The verifier does not learn any information about the information that the prover claims to know other than the assertion that she knows it.

Let’s look at a few examples demonstrating the concept of proving that you know something while leaking no knowledge of that thing. It sounds contradictory at first, but you’ll begin to see that it is not as strange as it sounds.

Example 1: Finding Waldo

“Where’s Waldo?” is a game where you have to find the titular Waldo (who looks like the image below) in a sea of characters and shapes that look like him.

Let’s assume that Peggy found Waldo and wants to prove to Victor that she knows where Waldo is — without revealing his location in the puzzle.

There are two ways she can do this:

Solution 1: Cut Out Waldo

Imagine that Peggy cuts out Waldo from the puzzle and shows Victor the Waldo cutout.

This begs the question. What if she just printed out a picture of Waldo and fooled Victor into thinking she found Waldo? How do we know she cut the snippet from the original puzzle?

To ensure that Peggy didn’t just cut out a picture of Waldo from somewhere, Victor can watermark the back of the puzzle. If Peggy’s cutout consists of the watermark, then Victor can be sure that Peggy did in fact find Waldo in the original puzzle.

Solution 2: Show Waldo Through a Hole

Imagine Peggy takes a very large and opaque piece of paper and cuts a small hole in it. She places the hole on top of the puzzle such that Waldo is visible through the hole. This shows that she knows where Waldo is, but Victor won’t be able to figure out Waldo’s location within the puzzle. You could imagine that the piece of paper is much larger than the original puzzle so figuring out the location of Waldo based on the cutout is not possible.

Completeness, Soundness and Zero-Knowledge

Now, let’s understand how these solutions satisfy the three properties.

Completeness

Recall that completeness means that a correct proof must be accepted. In either case, whether Peggy successfully provides a cutout of Waldo from a watermarked puzzle or uses a large opaque paper to display Waldo through a hole, Victor will accept the proof because he knows she can’t cheat.

Soundness

Soundness means that an invalid proof won’t be accepted. In solution one, by watermarking the puzzle, we make sure that if Peggy tries to fool Victor with a cutout of Waldo which doesn’t have a watermark, then he knows not to accept it. In solution two, we can ask Peggy to reproduce the original puzzle to make sure she is showing us Waldo from the original puzzle and not from a different one.

Zero-knowledge

Zero-knowledge means only the statement that is being proven is revealed. In either solution, Peggy is able to prove to Victor she knows the solution without him knowing where Waldo is (ie. Waldo’s location within the puzzle is never revealed).

Example 2: Color Blindness

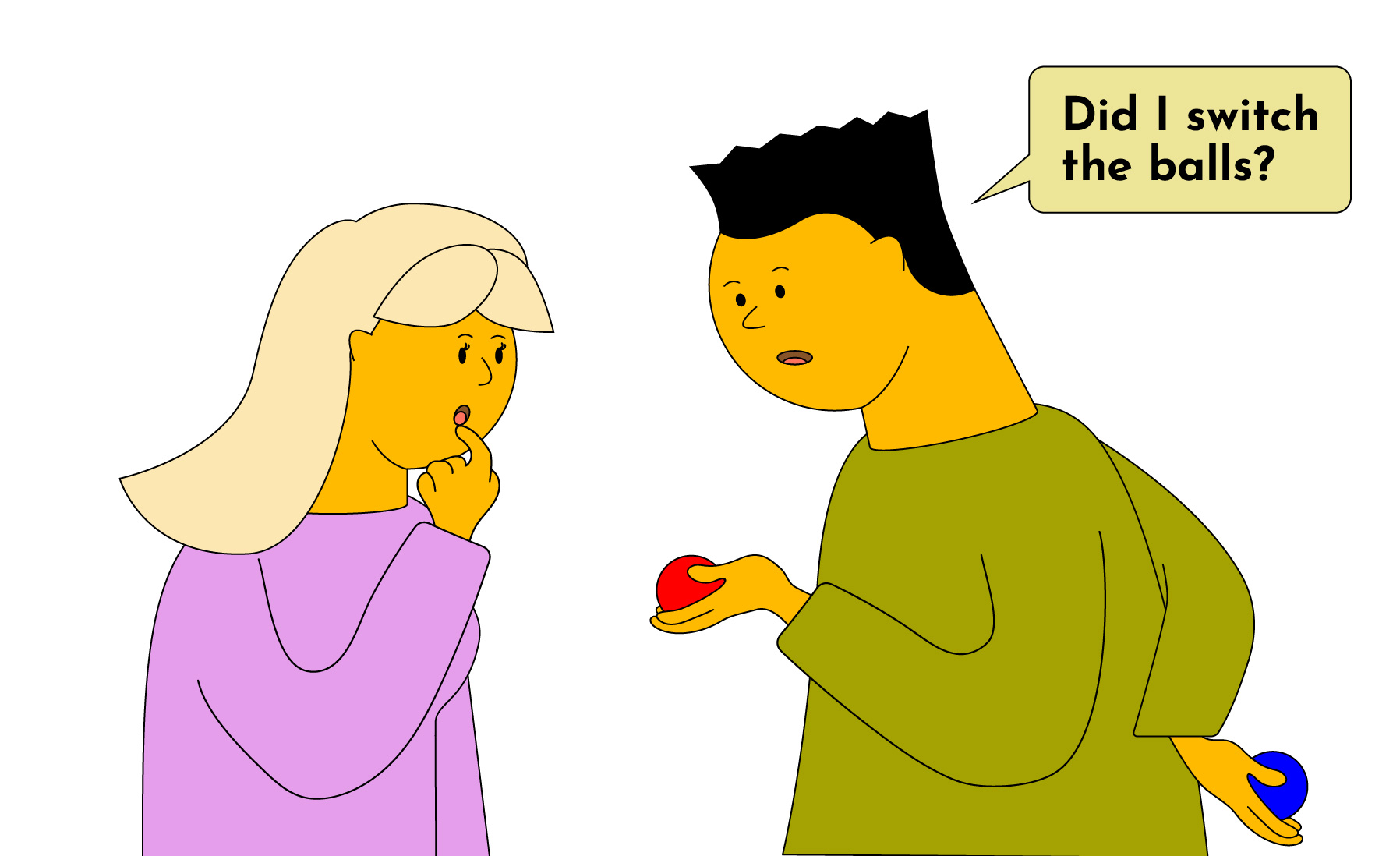

Imagine Peggy has two colored balls — one is red, and the other is blue. Since Victor is colorblind, he might not believe that the balls are different colors. Peggy, who isn’t colorblind, wants to prove to Victor that the balls are different colors, even though she can’t actually reveal the colors.

How can Victor verify Peggy’s claim?

Simple. Peggy takes the two colored balls and hands them to Victor. Victor puts both balls behind his back. He either switches the balls between his hands or lets them be in the same hand. He then brings the balls out from behind his back and asks Peggy, “Did I switch the ball?”

Since Peggy isn’t colorblind, she can confidently answer Victor’s question.

But she still hasn’t proven much. After all, the odds of being correct are 50%. Peggy could have gotten lucky with her first guess. So, Victor decides to repeat the process dozens of times. If Peggy provides the right answer, he can be sure the balls are different colors.

You’ll notice that, unlike finding Waldo, this example required many repetitions, where Peggy and Victor had to interact back-and-forth until Victor was convinced that Peggy was not colorblind.

The key point to take away from this example is that the zero knowledge scheme was probabilistic. While there isn’t a 100% guarantee that Peggy is not color-blind, if we run the process even just two dozen times, we can be 99.9999999404% certain that Peggy can see colors.

The probability of the incorrect answer is 1/2, so if we repeat the process n times, then the probability of getting it correct n times is 1 - 1/2^(n), where n is the number of repetitions. Real-world ZK proofs work the same way — they offer probabilistic guarantees of soundness and completeness.

Completeness, Soundness and Zero-Knowledge

Now, let’s take a look at how the above proof meets our three criteria:

Completeness

If Peggy is not colorblind, then by continuously giving the right answer to Victor about whether the balls are switched or not, she can prove to Victor that she can see colors.

Soundness

If Peggy’s claim is false and she is colorblind, then the probability of Victor accepting her proof is negligible because Peggy will eventually not be able to tell if the balls were switched or not.

Zero Knowledge

Victor has not learned about the actual colors of the balls, despite being able to verify that Peggy can distinguish the colors of the balls.

So, this solution works, but it definitely isn’t efficient or practical. It requires the verifier and prover to be available and interact repeatedly. Even if a verifier was convinced of a prover’s honesty, if another verifier wants to do the same, they have to start the whole interaction from scratch.

To solve this inefficiency, “non-interactive” proofs were invented. We’ll take a look at how these work in the next example.

Example 3: Hash function

Peggy knows some secret value “w” which, when hashed, results in “x.” Peggy needs to prove to Victor that she knows “w” without actually revealing “w.” Peggy can use a zero-knowledge proof for this.

We can convert the above scenario into a simple program:

function C(x, w) {

return sha256(w) == x;

}

The program takes in “x” (the hash of the secret value) and the secret value “w.” It returns true if the SHA-256 hash of “w” equals “x.”

So, Peggy needs to prove that she knows a value “w” that will result in the program above returning true.

The Basic Elements of Zero-Knowledge Proofs

In order to explain the solution to this problem, we need to understand the basic elements of zero-knowledge proofs — specifically “zk-SNARK” proofs.

zk-SNARK is an acronym that stands for “Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge.” Let’s break that down:

- ZK = Zero knowledge: We can prove a fact without revealing that fact.

- S = Succinct: The proofs for even very large programs are small (eg. a few hundred bytes) and can be verified within a few milliseconds.

- N = Non-interactive: There is no need for back-and-forth communication between a prover and verifier (eg. such as in the “Color Blindness” example above). Instead, a prover simply hands over a proof to the verifier and the verifier can compute whether the proof is valid or invalid.

- AR = Argument: For technical reasons, the proofs are called “arguments” because they are not technically “proofs” in the traditional sense — but they functionally serve the same purpose. The difference between “proof” and “argument” is very technical and out of scope for this post.

- K = Knowledge: This refers to the information that the prover knows.

Roughly speaking, a zk-SNARK consists of three algorithms: Setup, Verify, and Prove. We’ll take a look at each of them now.

Setup

The Setup algorithm generates two keys: the proving key (“pk”) and verification key (“vk”). In order to generate these keys, it takes as inputs a secret parameter (“lambda”) and a program C (such as the one we defined above, which returns true if the hash of “w” matches “x”).

The proving and verification keys created by the generator are public and used by the prover and verifier, respectively, to generate the proof and verify the proof.

Prove

The prove algorithm is responsible for generating the zero-knowledge proof. It takes as inputs the proving key (“pk”), the private witness “w,” and a public value “x” to generate the proof.

The witness (“w”) is the secret information that the prover claims she has knowledge of, while the value “x” is a value that is generated based on “w” but is obfuscated such that anyone can access “x” without figuring out “w.”

Verify

The verify algorithm is responsible for taking the proof created by the proving algorithm and asserting true or false, depending on whether the proof is correct or incorrect. It takes as inputs the verification key (“vk”), the public value “x,” and the “proof”.

Putting It All Together

Now, let’s revisit our problem statement. As a quick refresher, Peggy knows some secret value (“w”) which, when hashed, results in “x.” Peggy needs to prove to Victor that she knows “w” without actually revealing “w.”

Let’s see how this would look using a zk-SNARK, step by step.

Step 1: Generate the Program/Constraints

This is the program that tells us what knowledge we’re looking for. In our case, we have the constraint that the hash of “w” must equal “x.”

function C(x, w) {

return sha256(w) == x;

}

Step 2: Generate Keys

This requires us to select the secret parameter “lambda,” which must be done very carefully. If lambda is leaked, then anyone who has access to it can generate fake proofs. This is why zk-SNARKs require what is called a “trusted setup” phase where the keys are generated, but we have to trust that the lambda value was discarded properly and not leaked.

Step 3: Generate Proof

Peggy can now use the proving key, the hash of her secret value, and the secret value to generate the proof:

Step 5: Verify the Proof

Victor takes the proof, the hash of the secret value, and verification key and runs it through the verification algorithm to figure out whether Peggy's proof is valid or not.

And there you have it!

But before we wrap up, let’s check back in with our three criteria.

Assuming that we take the G, P, and V algorithms as black boxes, where we agree on the inputs and outputs and trust that the internals work as intended, then we can see how the solution exhibits completeness, soundness and zero knowledge.

Here’s how:

Completeness

The program “C” returns “true” when Peggy’s secret input value (“w”) is the right value. So, Peggy’s proof will be accepted by Victor.

Soundness

If the program “C” returns “false,” then the Verifier algorithm will return false and Victor will not accept the invalid proof.

Zero Knowledge

Victor is able to verify that Peggy knows “w” without gaining any knowledge of the value “w.”

Of course, the devil is in the details. Understanding how these black boxes work is not trivial, but not impossible either. We will be breaking down different components and aspects of zero knowledge technology in future posts.